Difference between revisions of "Additional Information"

m |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ''The below has been taken from the Breedcow and Dynama user manual version 6.02 Holmes WE, Chudleigh F and Simpson G (2017)'' | + | A presentation providing an introduction and overview of the basic economic principles applied to decision making on beef and sheep grazing properties can be viewed [https://futurebeef.com.au/projects/understanding-farm-management-economics/ here]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''The below has been taken from the Breedcow and Dynama user manual version 6.02 Holmes WE, Chudleigh F and Simpson G (2017)'' | ||

==Accounting and budgeting processes used in Breedcow and Dynama== | ==Accounting and budgeting processes used in Breedcow and Dynama== | ||

| Line 7: | Line 10: | ||

Beef cattle enterprises operate on a production cycle of up to five years for turnoff stock, and ten or eleven years for breeders. Cash flow budgeting measures usually cut the production cycle into segments of one year and cash transactions occurring in one year do not tell the whole story, since changes in herd composition also add value to the business or take it away. Keeping track of the livestock numbers and values enables inventory changes to be valued and incorporated in analyses of profit. | Beef cattle enterprises operate on a production cycle of up to five years for turnoff stock, and ten or eleven years for breeders. Cash flow budgeting measures usually cut the production cycle into segments of one year and cash transactions occurring in one year do not tell the whole story, since changes in herd composition also add value to the business or take it away. Keeping track of the livestock numbers and values enables inventory changes to be valued and incorporated in analyses of profit. | ||

| − | For this reason, the | + | For this reason, the Dynama+ program pays special attention to calculating herd structures and projecting stock numbers by age and sex. |

The budgeting processes of the Breedcow and Dynama suite of programs use the same concepts and measures of financial outcome as used in accounting, although accounting records and analyses past performance, while budgeting attempts to plan or predict future performance. | The budgeting processes of the Breedcow and Dynama suite of programs use the same concepts and measures of financial outcome as used in accounting, although accounting records and analyses past performance, while budgeting attempts to plan or predict future performance. | ||

| Line 71: | Line 74: | ||

*** Plant and improvements down $15,000, comprising a purchase of $10,000 (increase), a sale of $5,000 (decrease), and depreciation of $20,000 (decrease). ($10,000 - $5,000 - $20,000 = $15,000) | *** Plant and improvements down $15,000, comprising a purchase of $10,000 (increase), a sale of $5,000 (decrease), and depreciation of $20,000 (decrease). ($10,000 - $5,000 - $20,000 = $15,000) | ||

*** Term loans up $10,000, comprising new loans of $20,000, less loan repayment of $10,000 | *** Term loans up $10,000, comprising new loans of $20,000, less loan repayment of $10,000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Other examples of connections between worth and net income (not shown in the table) could include: | ||

| + | |||

| + | # Capital purchase (without depreciation), e.g. unimproved land, cost $50,000. What was cash at the start of the year becomes land of the same value at the end of the year. There is no effect on the calculation of net income, and no effect on net worth. | ||

| + | # Capital purchase of a depreciable item, cost $10,000, depreciation $1,000. What was $10,000 of cash in the opening net worth becomes $9,000 of asset in closing net worth. An extra $1,000 of depreciation is deducted in calculating net income, thereby reducing net income by that amount. Closing net worth is $1,000 less than it would have been without the purchase. Net income (hence also net income less drawings) is also $1,000 less than it would have been without the purchase. The reduction in net income less drawings is matched exactly by the reduction of closing net worth. | ||

| + | # Unspent net income of $10,000. If net income was $20,000, but only $10,000 was drawn, net worth at end of year would be $10,000 higher than at the start. The difference would be seen in the cash (or debt) accounts, unless the surplus was used for asset purchase, when it would show as extra non-cash assets. | ||

Latest revision as of 04:59, 12 June 2023

A presentation providing an introduction and overview of the basic economic principles applied to decision making on beef and sheep grazing properties can be viewed here.

The below has been taken from the Breedcow and Dynama user manual version 6.02 Holmes WE, Chudleigh F and Simpson G (2017)

Accounting and budgeting processes used in Breedcow and Dynama

The Breedcow and Dynama package is based on conventional accounting and budgeting concepts, as adapted to extensive beef cattle enterprises. The concepts of net income, the return on capital, net worth, gross margins and cash flow are employed in the construction of these software programs.

Breedcow and Dynama analyses are used to make better decisions on sales, investment and adoption or non-adoption of husbandry practices. Beef cattle enterprises operate on a production cycle of up to five years for turnoff stock, and ten or eleven years for breeders. Cash flow budgeting measures usually cut the production cycle into segments of one year and cash transactions occurring in one year do not tell the whole story, since changes in herd composition also add value to the business or take it away. Keeping track of the livestock numbers and values enables inventory changes to be valued and incorporated in analyses of profit.

For this reason, the Dynama+ program pays special attention to calculating herd structures and projecting stock numbers by age and sex. The budgeting processes of the Breedcow and Dynama suite of programs use the same concepts and measures of financial outcome as used in accounting, although accounting records and analyses past performance, while budgeting attempts to plan or predict future performance.

Tax accounting versus management accounting

Tax accounting uses rules which simplify the more comprehensive ‘management accounting’ but may end up giving a less than true picture of the financial result for that year. Examples include:

- The treatment of livestock trading accounts. For cattle enterprises, inventory values (the values of opening and closing stock) in tax accounts of $40 or $50 per head are typically shown, while the real values may be more like $400 to $400 per head. Tax based estimates of “net income” will thus be understated in years when cattle numbers increase and will be overstated in years when the herd is sold down.

- Balance sheet adjustments. Most assets will be shown at their original purchase cost or at unrealistically low written down values in taxation accounts (due to higher than actual depreciation rates being applied). Consequently the balance sheet may not give a true representation of the current value of the business and of the owner’s net worth. Major listed companies solve this problem by periodic asset revaluations (up or down) to ensure that the balance sheet shows a true picture, and a better one to present to a lender.

- Depreciation rates. Machinery has, in the past especially, been written off in taxation accounts at a rate well in excess of its real loss in value and some long lived water improvements have been written off either in one year or over three years. Consequently, most tax depreciation schedules now show only some of the plant and equipment still being used and some depreciation rates will be excessive. These effects might or might not cancel each other.

- Tax accounts may have the business spread over several accounting entities. One or more partnerships (or sole traders, or companies, or trustees) may own the land and the improvements on it, while another entity operates it.

Some grazing businesses address these shortcomings in the tax accounts by having their accountants prepare both management and tax accounts from the same set of figures.

The Breedcow and Dynama suite of programs (except Taxinc) assume the use of management accounting values and processes in all budgets. The accounting entity analysed need not be the same as analysed by the tax return(s). Livestock trading accounts are calculated with inventory values based on sale prices (these may be adjusted in Dynama+). Asset values and depreciation should be stated at realistic market (not tax) values.

How the accounting measures fit together

Key measures of business performance and position include net income (or net profit), cash flow, gross margins and net worth. Net profit is the primary measure of business performance and includes cash and non-cash components. It is a measure of outcome for a specific time period, e.g. the financial year 1st July 2011 to 30th June 2012.

In a beef business, net profit equals

- livestock trading profit, plus

- sundry income from other sources, less

- cash business expenses, less

- non-cash business expenses

The main non-cash business expense is depreciation, although the value of inventory change (plus or minus) may be included if there are variable quantities of fuel, fodder etc. on hand. (The value of livestock inventory change is dealt with in the livestock trading accounts).

Net profit represents a return to equity (net worth) and unpaid labour.

Livestock trading profit (or loss) also has cash and non-cash components. The cash component is the value of sales less purchases. The non-cash component is the increase or decrease in livestock inventory value. Cash flow, for a specific time period, comprises all cash coming into the business, less all cash passing out of the business. The cash flow calculation includes the cash components of net income plus any capital transactions plus non-business outlays (drawings).

A gross margin is a subset of net income. It is a measure used on one component of the business at a time, e.g. the cattle enterprise or the haymaking enterprise. The gross margin comprises the income from the enterprise, including inventory value increase or decrease, less the variable costs of the enterprise. The gross margin per unit of enterprise measures the effect on net income of adding or removing one unit of that enterprise.

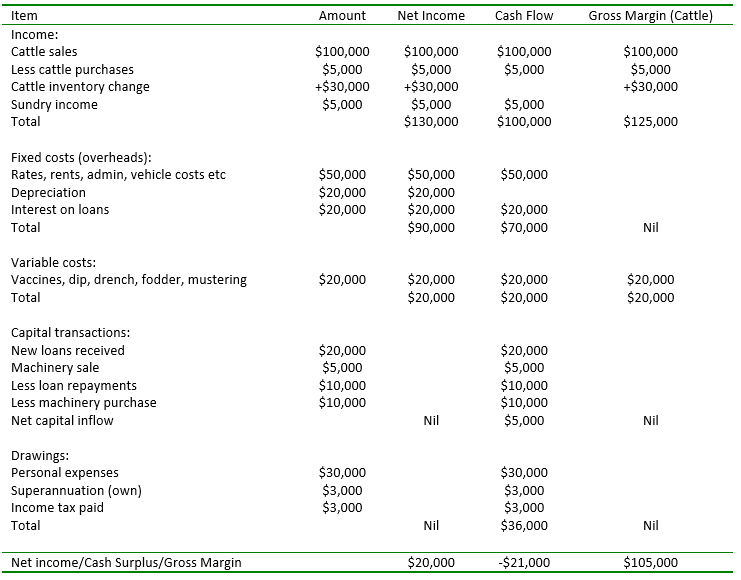

The relationship among net income, cash flow and gross margin is shown in the following table, using the same set of figures to compile all measures.

Note that the purchase and sale of machinery is a capital transaction, and therefore included in cash flow but not in net income – though those transactions will affect depreciation, which does feature in the net income calculation. Thus, over time, the cost of providing machinery (and other depreciable capital) for the business will be written off against net income as depreciation.

Net income as a concept is intended to measure the surplus generated by the business, over a period (normally a year), including an allowance for the change in the value of stock on hand. Depreciation can be viewed as just another example of allowing for change in the value of something used in the business (plant and improvements). Net income, as a measure, is used to assess the performance of the business, and to indicate to the owner the appropriate amount to distribute as dividends.

Cash flow is used mainly in budgeting to indicate future needs for new loans or future capacity to repay existing loans.

Net income measures change in wealth, while cash flow measures just the cash component of it.

A gross margin is used to identify the impact on the business of reducing or increasing the enterprise by one unit. For example, if the accounts shown in the table (above) relate to a business running 2,000 adult equivalents, gross margin per adult equivalent comes out at $52.50. Ignoring stocking rate effects on per head productivity, carrying one more adult equivalent would increase net income by $52.50; carrying one less adult equivalent would reduce net income by $52.50. This is because the gross margin includes only the income from the cattle enterprise, and only those costs that will change proportionately when enterprise size changes and which meet the test of one more animal equals one more unit of cost.

A gross margin is useful only if it can be compared with another gross margin. This comparison may be of gross margin per hectare from cattle versus sorghum. Alternately, it may be gross margin per adult equivalent from running the cattle one way, as against the gross margin per adult equivalent from running them some other way, given the same number of adult equivalents in each side of the comparison. It could also be gross margin per area when they are run at one stocking rate, versus gross margin per area when they are run at a different stocking rate (with productivity responses factored in). When comparing options for the business, potential improvement is measured by how much better the gross margin is for the “change” option versus the “without change” option. The budgeted difference in gross margins will be exactly equal to the difference in budgeted net incomes.

Net worth as at a certain date is a balance sheet measure. Net worth has already been defined as the total value of assets (including cash, livestock, land, and plant) less total liabilities (debts). There exists a mechanical link between net worth, net income, and drawings. If net income exactly equals drawings for the year, net worth at the end of the period will be the same as net worth at the start of the period (ignoring changes in underlying land values over the accounting period, which are handled by periodic asset revaluations).

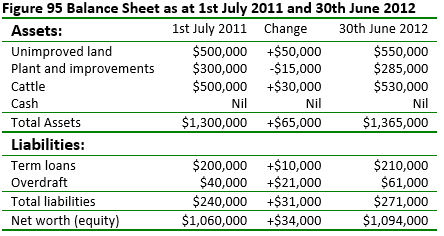

The following is an example of balance sheet, profit and loss and cash flow linkages, using figures from the previous table:

The balance sheet changes can be explained entirely by net income, drawings, asset revaluation, and cash flow. Net income for the year was $20,000, drawings were $36,000, asset revaluation (on land) was +$50,000, and cash flow was negative $21,000.

- Because drawings exceeded net income by $16,000, net worth would have gone down by $16,000, from $1,060,000 to $1,044,000, but asset revaluation (increase) of $50,000 brought it back up to $1,094,000.

- Because cash flow was negative $21,000, bank overdraft increased by $21,000 from $40,000 to $61,000.

- Component changes included:

- Unimproved land up $50,000 from $500,000 to $550,000 (asset revaluation)

- Plant and improvements down $15,000, comprising a purchase of $10,000 (increase), a sale of $5,000 (decrease), and depreciation of $20,000 (decrease). ($10,000 - $5,000 - $20,000 = $15,000)

- Term loans up $10,000, comprising new loans of $20,000, less loan repayment of $10,000

- Unimproved land up $50,000 from $500,000 to $550,000 (asset revaluation)

Other examples of connections between worth and net income (not shown in the table) could include:

- Capital purchase (without depreciation), e.g. unimproved land, cost $50,000. What was cash at the start of the year becomes land of the same value at the end of the year. There is no effect on the calculation of net income, and no effect on net worth.

- Capital purchase of a depreciable item, cost $10,000, depreciation $1,000. What was $10,000 of cash in the opening net worth becomes $9,000 of asset in closing net worth. An extra $1,000 of depreciation is deducted in calculating net income, thereby reducing net income by that amount. Closing net worth is $1,000 less than it would have been without the purchase. Net income (hence also net income less drawings) is also $1,000 less than it would have been without the purchase. The reduction in net income less drawings is matched exactly by the reduction of closing net worth.

- Unspent net income of $10,000. If net income was $20,000, but only $10,000 was drawn, net worth at end of year would be $10,000 higher than at the start. The difference would be seen in the cash (or debt) accounts, unless the surplus was used for asset purchase, when it would show as extra non-cash assets.