Dynama+ Assumptions

The concepts underpinning the Dynama+ program

The core of Dynama+ is a ten year livestock schedule that shows the annual flow of cattle through the herd. The flow of cattle and the performance described for the herd drives all of the outputs of the model.

Measures of profit and cash flow in Dynama+

The Dynama+ program calculates a range of financial measures that include both cash and non-cash components in their construction. The key measures calculated are net worth, cash flow for debt service, net income and return on total capital (in dollars and percent). The relationships between these measures and what they mean is discussed in detail in the appendix of this user manual. In summary:

- Net worth is calculated as the total asset value less total debt as at a particular date. Net worth is also known as “equity” and may be expressed as a percentage.

- Cash flow for debt service is calculated by deducting all cash outgoings (except loan service) from all cash inflows. Note that this differs from the definition of cash flow in the discussion of accounting measures in the appendix, which is net of debt service. In Dynama+, the cash flow for debt service is put first towards the service of term loans, with any surplus going into the working accounts and any shortfall funded from working accounts.

- Cash in and cash out include all cash components of the net income calculation, plus items of a private or capital nature that are not part of the net income calculation. The latter include family living expenses and taxation, capital expenditures, receipts and other capital transactions including gifts given or received and transfers to or from other accounting entities.

- Depreciation and livestock inventory change, which are part of the net income calculation, are not included in the cash flow calculation since they are not cash.

- Net income is defined in Dynama+ as being equal to gross income, including the increase or decrease in livestock inventory value, less all variable and fixed costs including interest and depreciation. Net income includes some non-cash items (inventory change and depreciation) and excludes some cash items (tax, family expenses, capital transactions and loan reductions). Net income is thus not the same thing as net cash flow.

- Depreciation is the annual provision made in profit budgets to spread the cost of capital items such as vehicles, machinery and fences over the period of use of these items. Such capital costs, rather than being charged against net income as they occur, are smoothed over time and charged annually as depreciation. These capital costs will show up in a cash flow budget (and in Dynama) as lump sum outlays. If funded by borrowing, there will also be a cash inflow as the loan is received, and a series of outflows as the loan is repaid. Leased capital does not show up in the depreciation calculation (or in the balance sheet) but appears as a lease payment in the calculation of net cash flow or net income.

Budgets constructed in Dynamaplus need to observe the limits on stocking rate (adult equivalents), working account balances and total debt that apply in the real world of the beef enterprise being modelled.

Profit versus cash flow

A profit and loss statement is one of the three main ways used to look at overall business outlook and performance - the cash flow budget (or statement of sources and uses of cash) and the statement of assets and liabilities being the other two.

Cash flow statements and budgets are regularly drawn up to monitor or predict short term cash flow but looking at short term cash flow on its own can paint a very misleading picture of the direction of a beef business. A cash-flow statement /budget show the cash expected to come into and go out of a business over a given period. It can indicate the amount of working capital that may be needed from outside sources and whether it is possible to fund the production cycles of the business within the current borrowing limits negotiated with the lender.

A cash-flow budget can bear little relationship to the actual profitability of the business as it may include things like capital income and expenditure, new loans, off farm income and personal expenses. A cash-flow budget also does not reflect the non-cash items such as unpaid operator’s allowance, depreciation or increases/decreases in the value of inventories. Estimating these things in a profit budget allows a more accurate estimate of how efficiently resources are being used.

Profit and loss statements or budgets are constructed to estimate the profit of a business over a given period so therefore focus on the efficiency of resource use within the business. It can be argued that profit can only really be measured once the investment is finalised and all of the inflows and outflows accounted for. As most beef businesses have an effective investment life that may span decades, the estimates of profit derived will apportion values to capital at the start and end of the time period of the analysis. In this way any improvement in the underlying value of capital or a change in the livestock and plant inventory due to a change in strategy can be included in the estimate of profit made.

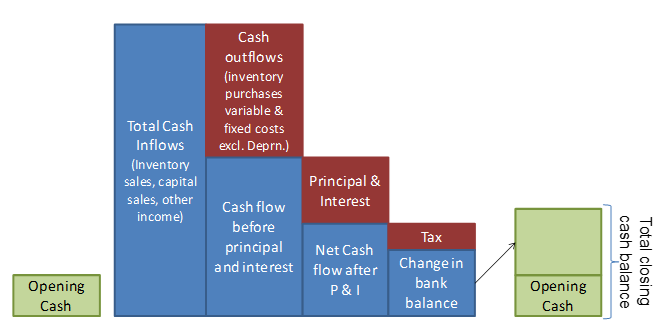

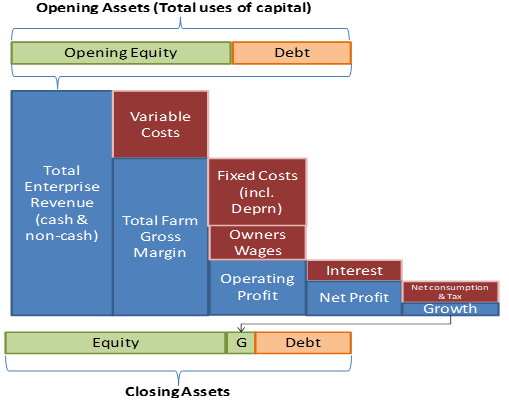

Figures 26 and 27 indicate the differences in the standard measures of farm performance when profit and cash flow are being considered. Figure 26 identifies the various components of how we estimate profit (efficiency). The direct links between the change in equity over the period and profit can be identified.

The important thing about Figure 26 is the direct link between profit and growth in wealth.

Figure 27 indicates the calculation of liquidity and the net cash flow before and after debt servicing. When Figures 26 and 27 are taken together they represent the balance sheet of the business, the profit and the net cash flow.

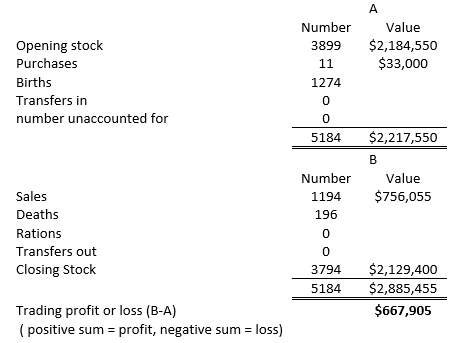

Figure 28 provides a typical layout of a livestock trading schedule compiled to calculate the trading profit of loss on a beef enterprise. Note that livestock sales does not always (rarely) equals livestock trading profit.

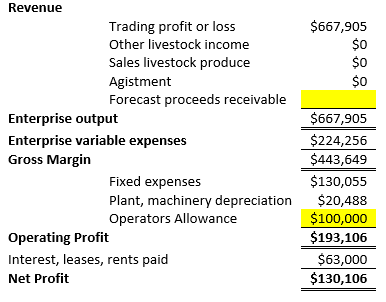

Figure 29 shows the profit analysis for the example beef enterprise. The trading profit or loss calculated in the schedule is transferred to the profit and loss statement.

A livestock gross margin is the gross income from an enterprise less the variable costs incurred in achieving it. It excludes fixed or overhead costs.

The total cash costs need to be allocated to five main subheadings when profit is being calculated and profit budgets are to be prepared:

- Variable costs: costs which change according to the size of an activity. The essential characteristic of a variable cost is that it changes proportionately to changes in enterprise size (or to change in components of the enterprise). Variable costs are the total of selling costs and husbandry costs in Breedcow and Dynama.

- Fixed (or overhead) costs – These are defined as costs which are not affected by the scale of the activities in the farm business. They must be met in the operation of the farm. Examples include: wages and employee on-costs, repairs, insurance, shire rates and land taxes, depreciation of plant and improvements, consultants fees, operators allowance for labour and management. Some fixed costs (like depreciation or operator’s allowance) are not cash costs and will be estimated for inclusion in the calculation of operating profit. It is also usual to count the smaller amounts of interest paid on a typical overdraft or short term working capital as an operating expense (fixed cost) and deduct them in the calculation of operating profit. In a profit analysis, the larger amounts of interest or leases are defined as the returns to lenders of fixed capital and not as a cost. They are deducted in the calculation of net profit as non-operating expenses.

- Non-operating expenses (including the returns to lenders of fixed capital) - These are items unrelated to the farm business operational activity. They generally cover the amounts allocated to such things as interest, rent and leases. They include amounts paid by the business for the use of capital provided by various lenders of capital external to the business and are deducted from operating profit to calculate net profit.

- Personal costs - Family and other personal costs not incurred in operating the business and would largely continue if the business was wound up.

- Capital costs - purchases of significant capital equipment. The cost to the business of capital equipment is apportioned as depreciation in a profit analysis. Depreciation is a form of overhead or fixed cost that allows for the use / fall in value of assets that have a life of more than one production period. It is an allowance deducted from gross revenue each year so that all of the costs of producing an output in that year are set against all of the revenues produced in that year.

Profit terms

Operating Profit: is the return to total capital invested after the variable and overhead (fixed) costs involved in earning the revenue have been deducted. Operating profit represents the reward to all of the capital managed by the business.

Operating profit = (total receipts – variable costs = total gross margin) – overheads

When operating profit is expressed as a percentage return to total capital it indicates the efficiency of the use of all of the capital managed by the farm business.

Net Profit = Operating profit less the returns to outside capital (and other non-operating expenses). As the returns to lenders of fixed capital (interest, rent and leases) are deducted from operating profit in the calculation of net profit, it therefore represents the return to the owner’s capital.

Net profit minus income tax minus personal consumption (above operators allowance if it has already been deducted from operating profit) = change in equity. Net Profit is available to the owner of the business to pay taxes or to provide living expenses (consumption) or can be used to reduce debt. (See figure 27)

When net profit is expressed as a percentage return to the owners capital it indicates the efficiency of the use of the owners capital invested in the farm business.

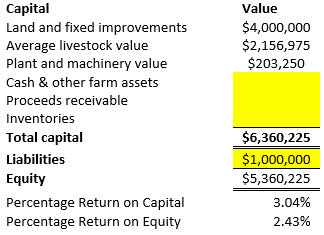

Figure 30 shows a typical calculation for the percentage return on total capital, one of the main efficiency criteria for a beef business. It is calculated by dividing the operating profit by the total capital managed. The percentage return on equity is calculated by dividing the net profit by the owners’ equity and represents how well the owner’s capital preformed.

How useful a measure is the percentage return on total capital or the percentage return on equity? When a change is being considered it is probably better to look at the return to the extra capital being invested not the total capital invested. This is unless the change being considered is to shift all of the capital out of the current beef business.

The profit statement shown in Figure 30 is once again a snapshot that can be useful information but does not give us much guidance as to the best strategy to follow in the future. We will apply investment and cash flow budgets to do that task. The absolute and relative value of historical Operating and Net Profit may tell us something about the capacity of the business to fund change but tells us nothing about which change in management strategy may make the most improvement in the profit generated by the business.

The analyses included in later exercises will apply a partial discounted cash flow budgeting method that looks at the difference between two strategies over time. This is done in the Investan program.

Notes

- ↑ Source: The Farming Game: Agricultural Management and Marketing by Bill Malcolm, Jack Makeham and Vic Wright., Cambridge University Press, 2005.